One of the challenges hygienists experience in daily clinical practice is patient acceptance of nonsurgical periodontal therapy. The scenario often looks something like this: The patient is scheduled for a dental prophylaxis, and upon completion of radiographs and full periodontal charting, it is discovered that the patient has active periodontal disease. The hygienist informs the patient that he or she needs a deep cleaning. The patient then states that he or she just wants a regular cleaning. At this point, a standoff may ensue. The hygienist tells the patient that he or she cannot have a regular cleaning. The patient states he or she will not consent to a deep cleaning. Patient and provider are at an impasse. Everyone has their defenses up, and no one is willing to budge.

So, what can be done to de-escalate the situation or—even better—avoid it in the first place? When 45.9% of the adult population 30 years of age and older have periodontal disease,1 dental providers will find themselves in this position countless times each year. There are some specific communication strategies and modified language skills that can help the provider to sidestep a dental standoff. By positioning yourself as a patient educator and ally, you can bridge the gap between recommendations and results.

Upon deeper examination of the commonly used terminology during a hygiene visit, it becomes apparent that much of the benefit-based language has been removed. For instance, a dental prophylaxis is often referred to as a cleaning. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the word prophylaxis is defined as “measures designed to preserve health and prevent the spread of disease; protective or preventive treatment.”2

When we, as dental professionals, tell our patients that we are scheduling them for a cleaning, we completely ignore the benefit they will receive, which is to protect their oral health by providing preventive care. Similarly, what is a deep cleaning? There is no reference of treating a disease process. The terminology of scaling and root planing or deep root scaling describes what the provider is technically doing, but there is still no benefit-based language regarding what the procedure is accomplishing for our patients. Do we want to use language that demotes us from health-care providers to tooth janitors and ignores the entire purpose of the procedures we perform for our patients?

While the intent of using phrases such as deep cleaning is to help patients understand the procedure, true education of the condition and treatment are better served with language that reflects why the therapy is recommended. We can speak on a level our patients can understand without discounting or overlooking the purpose and importance of the recommended procedures.

When deciding what terminology to use when you are educating your patients, it can be helpful to ask yourself, “What is the benefit of this service?” Instead of periodontal probing, consider saying gum health assessment. Permanent bone damage is more compelling than bone loss. A deep cleaning becomes gum infection therapy. When patients hear that they need a special therapy to address the infection in their gums to stop any additional permanent bone damage from occurring, they will likely be a lot more concerned about their condition and open to treating it than if they were simply told they need a deep cleaning.

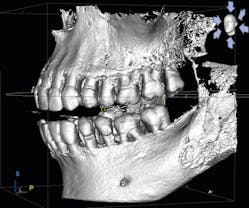

Telling patients they need a specific treatment is not enough, however. High-level record gathering and communication of findings are critical for patients to grasp the effects of their condition. Helping patients own their condition is the first step toward guiding them to accept treatment. The records I have found to be helpful in this aspect are bitewing radiographs, a series of intraoral photos, complete periodontal charting, and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). Not only are these records helpful for the detection of disease, they also provide an invaluable opportunity for cooperative discovery. Through this process, patients are involved in the review and evaluation of their records, and they can observe firsthand the concerns as they are discovered (figures 1 and 2).

I have found that patients are more easily able to understand why they need periodontal therapy if they can see the active disease process and damage within their own mouths, as opposed to generic photos or explanations in chairside educational materials. I like to turn my patients around in the chair so they can see the screen as I actively evaluate their records. I talk patients through the process as I complete periodontal charting and assess their bitewings, CBCT, and photos. I use readily understandable language to explain any concerns I see. A few times throughout the process, I will ask the patients what questions they can think of. By the time any recommendation is made, my patients are fully aware of why treatment is needed.

If patients ask why they cannot have “just a cleaning” after this entire educational process, it is easy to explain that a regular cleaning is truly preventive treatment to protect from disease, but since disease is already actively present, prevention is no longer an option. It is not possible to prevent something that has already occurred. You can also explain to your patient that by scaling only supragingivally (as with a regular “cleaning”), you would be doing them more harm than good in the long run.

I have found that using the phrase “I am concerned” and genuinely meaning it can be helpful. For example, “Mrs. Jones, I am concerned that if we only clean above the gums and leave the infection underneath, you will suffer more long-term damage not only to the bone that holds your teeth in, but also potential damage to the rest of your body.” This is the perfect time to talk about the oral-systemic link and the correlation between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease, as well as diabetes.

By partnering with your patients in the pursuit of oral health and by using thorough education through cooperative discovery, you can count on your appointments going much more smoothly. Instead of facing the dental standoff, you will be empowering patients to make decisions for their oral and whole-body health. While using new terminology can be uncomfortable at times, adaptation on our parts is much less troublesome than a stalemate regarding treatment or—even worse—total rejection of treatment. Education and understanding are paramount in achieving acceptance of treatment recommendations. It is within your reach to achieve success in patient education and periodontal treatment acceptance. Will you choose to be the ally your patients need and deserve?

References

1. Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2015;86(5):611-622. doi:10.1902/jop.2015.140520.

2. Prophylaxis. Merriam-Webster website. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/prophylaxis?src=search-dict-box. Published 2019. Accessed May 18, 2019.